Son’s overdose evokes ODA vice president to educate dentists about opioids

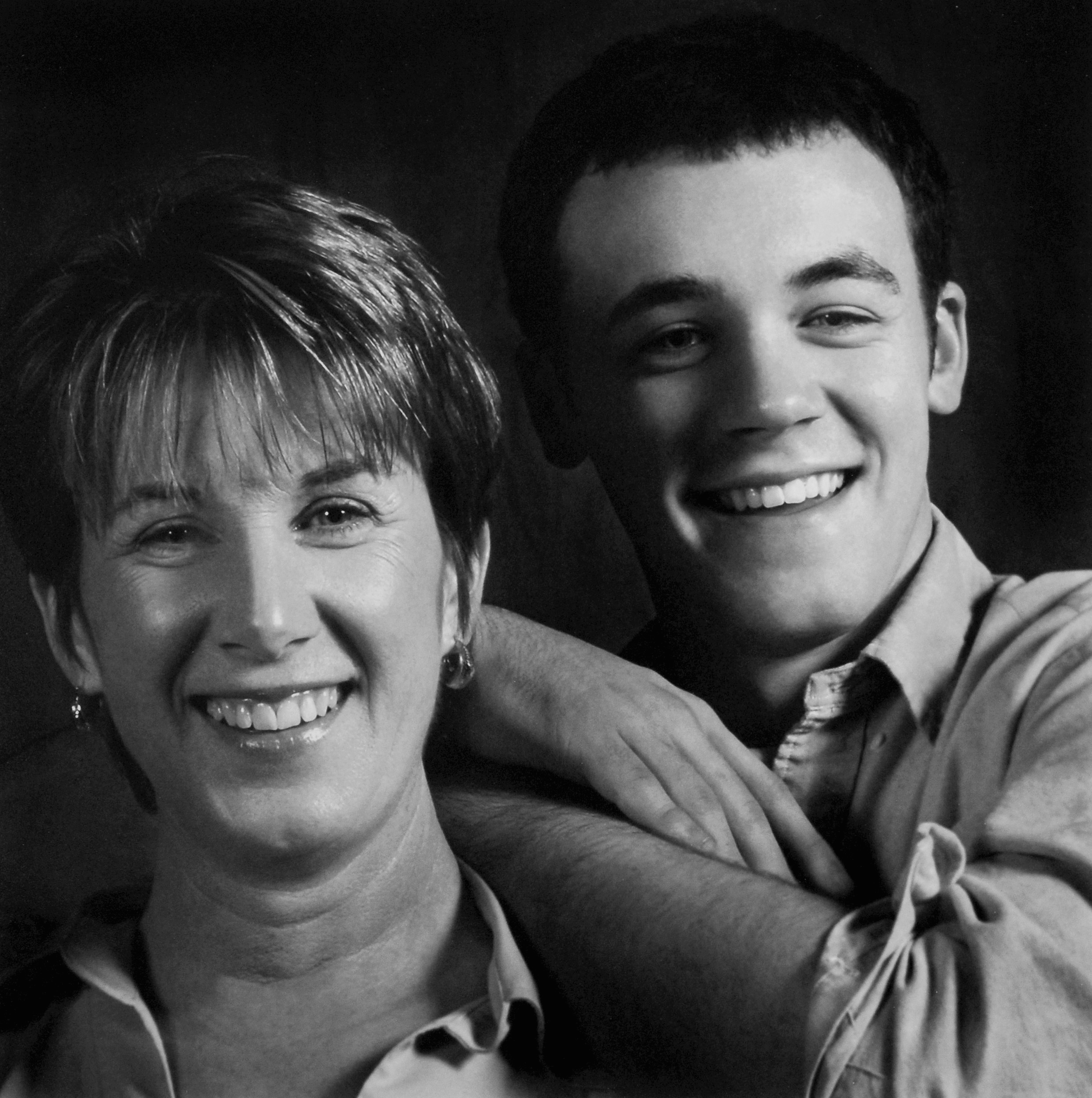

ODA Vice President Dr. Sharon Parsons with her son Sean Herman who died from an overdose in 2016.

More than 170 people die each day from drug addiction in the United States. One of those is Sean Herman, the son of Ohio Dental Association Vice President Dr. Sharon Parsons. He died from an overdose in 2016.

Since then, Parsons has worked to educate dentists on the potential dangers of over prescribing opioids and how addiction is affecting families.

“I want people to understand more about addiction,” Parsons said. “And I want them to realize that we know very little about addiction as health care providers. Dentists and physicians both get very little education about addiction.”

Herman was a typical kid who excelled academically and was active in sports growing up.

“Sean was extremely bright,” Parsons said. “He was in the gifted program in elementary, middle and high school. And he had a wicked sense of humor. But he wasn’t always innocent either – in high school he definitely snuck beer and pot, all those things boys will do that their mom doesn’t want them to do.”

Herman was accepted into the Scholars Program at The Ohio State University and was a political science major. During his junior year, a friend invited him to ride dirt bikes on a farm. Although Parsons warned him against going because it was finals week, he went anyway. He got hurt, but didn’t seek medical attention.

“A guy in the house next door handed him some pills and said ‘take these, you’ll be fine.’ And that was the beginning,” Parsons said.

It didn’t take long, and he became addicted to OxyContin.

She said she could notice a difference in how he acted – he seemed not totally with it or like he was half a beat behind. She asked him several times about what was going on, and after pressing him he eventually told her about his addiction.

He went to rehab and came out clean, but he quickly fell back into addiction, Parsons said. He learned that heroin is the same as opioids but easier to find and less expensive, and he soon began shooting heroin.

“That’s a whole different world,” Parsons said.

She said he went through periods of being clean and then back into addiction, known as the “addiction waltz” that happens to many addicts as they keep repeating steps one, two and three in recovery programs.

During one period of sobriety where he was seeing some success with staying clean, Herman went on a white water rafting trip with his NA group, and hurt himself on the trip. He had ankle surgery, and the doctor prescribed him narcotics. His addiction started up again.

Shortly before he died, he seemed to be on a path to getting clean again. He had gone through detox and had gotten a job. Parsons had agreed to let him move back in with her because he seemed to be doing well. He began moving in with her on a Saturday night in September and planned to finish moving in on the following Monday.

But on Sunday night, he overdosed on a drug laced with fentanyl and passed away.

“The fall out was really huge,” Parsons said. “The collateral damage, so to speak. It not only affected my son, it left my whole family without a family member.”

Parsons’ mother died later that same day, and doctors believe that she had a heart attack from the shock of what happened with Herman.

“Just one handful of pills devastated my family,” she said. “If we can find other means to help combat pain, I think we can help prevent a lot of future problems. I want people to know it can happen to anyone. Addiction doesn’t discriminate. There’s hardly anyone who has not been touched by someone being affected by drug addiction.”

Parsons said dentists should not assume they have not contributed to addiction because oftentimes they may never know whether or not a patient has become addicted to opioids after receiving a prescription.

“My son was so ashamed, if he got something from a doctor he would have never gone back to that provider for more,” Parsons said. “People don’t know whether they’ve been the initial thing that got someone addicted or not. Just because no one has come back to you asking for more, that doesn’t mean what you prescribed didn’t cause a problem.”

People between the ages of 13 and 26 are most at risk for becoming addicted to opioids because their brains are still forming, Parsons said.

“In that age range, if exposed to an opioid, you’re five times more likely to become addicted,” she said. “That’s middle school, high school, college sports and wisdom teeth removal. I would really caution people about prescribing opioids to that age range.”

Parsons said she wants to emphasize to dentists the importance of educating themselves about prescribing opioids and the risks of addiction.

“Dentists don’t realize how big of a role we actually played in creating the problem,” she said. “No one did it on purpose, I think they just didn’t know, and that’s why we need to become educated so we do know in the future. Some people do just decide to try heroin, but the vast majority use heroin when they can’t afford opioids, and the majority does not survive. Our goal is to try to create fewer future addicts.”

Over the last couple of years, Parsons has been working to educate dentists by speaking to groups about opioid addiction along with her friend and colleague Dr. David Kimberly, who is an oral surgeon in Akron.

Parsons and Kimberly now present CE on opioid prescribing to dentists in Ohio. Their first presentation took place at the 2017 ODA Leadership Institute.

Parsons’ younger son, Michael Herman, was in his first semester of dental school at University of Detroit Mercy when his brother overdosed. Parsons said he has become an advocate on this issue as well, and they plan to speak at the dental school together in the future about opioid addiction.

Parsons said that the parents of addicts are watching health care providers and specifically dentists very closely to see how they are responding to the opioid epidemic. She said many parents are mad, and they feel that their children’s addiction began when they got their wisdom teeth out. She said organized dentistry is in a good position to help change the perception and present dentists as responsible prescribers.

Kimberly agreed. “Organized dentistry has allowed the dental profession to speak with one voice to the public and to the legislature showing that dental professionals are responsible and concerned health care practitioners,” he said.

One way the ODA is working to improve this perception and help curb opioid prescribing is through an Interim Policy on Opioid Prescribing that was passed by the Ad-Interim Committee in March, Parsons said. The policy supports opioid prescribing CE for dentists, among other things.

Parsons said it’s also important that we change the conversation about opioids.

“I want people to know it can happen to anyone,” she said. “I want them to be open-minded and not judgmental. There was such a stigma associated with this that my son was very ashamed for a long time and didn’t want to talk about it. I was more open than he was. If the stigma had not been there, he probably would have gotten help sooner. We have to be open about it and talk about it.”

Looking for more information about opioid prescribing and addiction?

Attend “The Heroin Epidemic, Prescription Drug Abuse and Your Practice” from 10 a.m. to noon Sept. 15 at the ODA Annual Session. Register and learn more at www.oda.org/events with course code S70.